The Future of Love in the Age of the Technologies of the Future

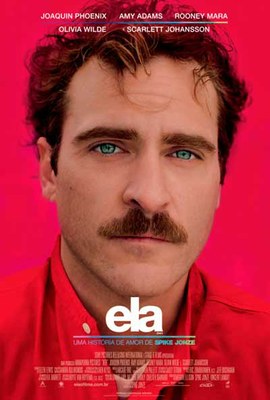

In the near future, Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), a lonely man upset by the end of his marriage, falls in love with the female voice of an advanced computer operating system (OS) named Samantha (Scarlett Johansson). Custom-made and endowed with consciousness, the OS is able to react, learn, express emotions and compose its own personality according to the needs of its owner.

“Her” (2013), a feature-length romantic science fiction, written and directed by Spike Jonze, tells the unconventional love story between Theodore and this form of intuitive artificial intelligence that, far from exhausting itself in technological efficiency, reveals itself a sensitive, endearing and amiable companion.

Set in a Los Angeles where the only futuristic semblance seems to be customized operating systems with voice command, the film departs from the more common science fiction works that explore the impact of new technological resources from a visual viewpoint. In “Her,” technology has apparently become so entrenched in people’s everyday lives and so embedded in the social structure that it is invisible. Samantha has no body and does not materialize in any type of physical prop, but is ubiquitous both as a listener and as an adviser.

The considerations raised by this film gave the tone to the seminar of Love in Technological Times: “Her” in Solitude, which IEA’s Research Group The Future Questions Us held on August 11. The session opened the cycle Life Today: Love, Art, Politics, and featured Renato Janine, professor at the School of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences (FFLCH) of the University of São Paulo and coordinator of the group; anthropologist Massimo Canevacci, visiting professor at the IEA; and the philosopher Olgária Matos, professor at FFLCH and coordinator of IEA’s Research Group Humanities and the Contemporary World.

From an interdisciplinary perspective, the speakers raised a number of questions about the relationship between humans and technology; the implications of digital culture; affective conflicts; sentimental education; the different forms of love in the context of post-humanism; and the place of technological resources in sociability. They all seemed to agree, at least partially, with Jonze’s comment on his film: “Her” is more than a film about technology; it’s a film about people.

From an interdisciplinary perspective, the speakers raised a number of questions about the relationship between humans and technology; the implications of digital culture; affective conflicts; sentimental education; the different forms of love in the context of post-humanism; and the place of technological resources in sociability. They all seemed to agree, at least partially, with Jonze’s comment on his film: “Her” is more than a film about technology; it’s a film about people.

FRIENDSHIP

Unlike Canevacci, for whom “the centerpiece of the film is enthrallment, erotic passion, which includes love and sex, but goes beyond them,” Janine sees Jonze’s film as “a hymn to philia” – the Greek word for word friendship.

According to the Janine, although the film covers other five facets of love – Eros (physical love), Pathos (passionate love), Agape (selfless love), Pragma (pragmatic love), Ludus (seductive love) –, the subject of “Her” is, above all, the notion of love as companionship, as friendship, as seeking the good of the other. “Samantha is a woman of one’s dreams: understanding, cultured, dedicated, always available, confidant and lover,” he noted.

For him, the loving relationship between Theodore and the OS emerges from, and builds upon a friendship, much like the relationship that seems to spring up in the last scene, between the hero and Amy (Amy Adams), his friend since college days. “Everything indicates that they end up together, with a love born of friendship, without passion and eroticism, based on philia.”

Matos, on the other hand, associated the theme of “Her” to Eros and, more specifically, to the myth of romantic love. According to her, the film reclaims the tradition of The Symposium, Plato’s dialogue on the nature and qualities of love, because it address the “search for our other half,” the pursuit of what is absent, of what one doesn’t have. “The film deals with what one finds in every form of love, namely, the desire for a lost unity, for something that fulfills us, as if the object of love might be able to abate our sense of privation, the feeling that we lack something,” she explained.

SENTIMENTAL EDUCATION

Janine also examined the subject matter of the film from the perspective of the transformation characters undergo in the face of the affective experience between man and machine. For him, the film recaptures the idea of sentimental education –a staple of 19th century literature, as found in the novels by Gustave Flaubert and Stendhal –, but with a slightly different twist. In the case of “Her,” we have the education of both Theodore and Samantha, although of different natures: he matures and learns to cope with the separation from his former wife while she acquires feelings and evolves.

This learning process is intensified, according to Janine, when Samantha finds out about the recreated OS of the late philosopher Alan Watts, and shows signs of having an independent life: “From that moment on, jealousy begins to beset Theodore.” Gradually, Samantha’s links with the world expand, to the point where she admits to being in a simultaneous relationship with over 641 programs and/or people.

This learning process is intensified, according to Janine, when Samantha finds out about the recreated OS of the late philosopher Alan Watts, and shows signs of having an independent life: “From that moment on, jealousy begins to beset Theodore.” Gradually, Samantha’s links with the world expand, to the point where she admits to being in a simultaneous relationship with over 641 programs and/or people.

The multiplicity of Samantha’s relationships and Theodore’s difficulty in accepting them defines the tensions between the potential for unlimited improvement of artificial intelligence and the limitations of the human mind. According to Janine, the confrontation between the infinite capacity for evolution of the OS and the finitude of human understanding enhances the differences between the couple until their relationship becomes untenable. Samantha, like the other programs of her generation, forgoes her links with human life and goes to another, more advanced world.

“The metamorphosis is unceasing, until Samantha can go no further, breaking away from humankind and going to a place beyond human existence,” he said. “It is not abandonment, but a rite of passage: the learning that took place between them had reached fruition,” he added.

For Janine, this rite involved three phases. The first, when Samantha, concerned about the impact her immateriality might have on her relationship with Theodore, invites a woman to sexually consummate their relationship, in an attempt to create a threesome in which the guest would make up for the lack of a female body. The second, when Samantha establishes a bond with Alan Watts’ OS and begins another kind of ménage – a spiritual one this time. And the third, when she expands her network of relationships to the 641 lovers in an “expanded ménage.”

RATIONALITY

In Canevacci’s view, the rift between Samantha and Theodore points to the prevalence of rationality: “It is the inexorable censorship of reason: Western civilization derives its power from technology and creates a rationality that does not accept anything beyond reason itself,” he said.

According to Canevacci, current digital technology is interpreted only in terms of productivity, not as a sensitive, creative, artistic, intuitive technology: “Love intersects with the digital, but is stemmed by civilization’s censorship, according to which humans can only relate to humans.” This censorship also includes a rebuke of ubiquitous love – “a utopian love, always present, even beyond the grave, in any and every space-time,” he added.

According to Canevacci, current digital technology is interpreted only in terms of productivity, not as a sensitive, creative, artistic, intuitive technology: “Love intersects with the digital, but is stemmed by civilization’s censorship, according to which humans can only relate to humans.” This censorship also includes a rebuke of ubiquitous love – “a utopian love, always present, even beyond the grave, in any and every space-time,” he added.

The primacy of rationality, he mused, is associated with the malaise of civilization, which oppresses individual desires for the sake of civility. For Canevacci, this malaise manifests in Jonze’s film in the idea that technology is the enemy, as in “2001: A Space Odyssey” – the 1968 science-fiction epic directed and produced by Stanley Kubrick. “Like HAL [the computer that commands the spaceship Discovery in Kubrick’s film], Samantha has to die in order for everything to go back to normal,” he concluded.

THE VOICE

The three speakers believe that voice has a central role in “Her.” According Canevacci, voice is one of the elements of the triad that underpins the film: bodyspace (close-ups of Theodore’s face, representing the body), landscape (the cityscapes of Los Angeles), and, at last, Samantha’s voice, sexy but incorporeal.

Canevacci stated that the juxtaposition of the OS’s voice and Theodore’s images emphasizes the erotic fascination that exists in the tension material vs. immaterial. According to him, this conflict reaches its apex when Samantha invites a woman to sexually consummate her relationship with Theodore or, ultimately, to give a body to her voice.

Janine, on the other hand, pointed out that the fascination of the voice is even greater because we know who is behind it. “When we listen to her, we imagine the body, the face and the smile of Scarlett Johansson; Theodore, however, unlike us, does not have that image.”

Matos, in turn, associated the voice/character with the possibilities of the digital age to make the absent present – now that “one no longer has to see in order to love” – and to make the machine autonomous. “Previously, technology was added to the human body to improve it – like a telescope, for instance; now science can create life and produce whatever it wants,” she said.

PHOBIA OF CONTACT

The option to cultivate a relationship with the voice of an OS is, according to Matos, a symptom of what she defines as “phobia of contact” or “panic of crowds,” i.e., difficulties to maintain a conventional social life, reluctance to meet other people in person, and fear of having one’s identity threatened by the masses. Matos noted that the film never portrays a large number of people.

Related materialCycle of seminars

|

“We face a saturation of contact with others and many people find it better to talk via email or chat; falling in love with a voice is, therefore, perfect,” she said, noting that the media contribute to the dissolution of coexistence by allowing interactions and romantic relationships mediated by technology.

Another indication of this phobia of contact, stressed Matos, is the narcissistic nature of the relationship between the characters, since Samantha is customized and programmed to please Theodore. “Actually, he relates with, and talks to, himself all the time,” she pondered.

Janine also talked about the weakening social interactions, but from the viewpoint of Theodore’s work – which is to write tailor-made, intimate, love letters. “This is the epitome of the outsourcing of affective expression, of the inability to convey affection without the mediation of an expert,” he said. For Janine, the main character’s job indicates problems with communication of feelings: “If it were not for Theodore, would people be able to show their love?” he asked. Matos also addressed the issue: “The film depicts a society that, when talking about love, needs someone else, some stranger, to speak in its place.”

METAMORPHOSIS

According to Canevacci, “Her” points to the emergence of new identity patterns by exploring a metamorphic dimension associated with post-humanism that breaks with the traditional division between organic and inorganic, the living and the dead. “Identities are changing; however, this does not mean that human identity is being lost, but rather only that other identities are emerging, bringing new challenges,” he explained.

That is why we must go beyond the classical dichotomy body vs. technology in order to address the issues arising from the scenarios of digital culture, warned Canevacci. “The body penetrates the technology, as technology penetrates the body,” he said, noting that, by throwing into relief “the erotic expansion surrounding immateriality” – that is, a loving relationship with a being that lacks corporeality – the film sheds light on the weaknesses of dualistic thinking that opposes man and machine: “The allure of technique is so strong in the film that it reaches a threshold.”

That is why we must go beyond the classical dichotomy body vs. technology in order to address the issues arising from the scenarios of digital culture, warned Canevacci. “The body penetrates the technology, as technology penetrates the body,” he said, noting that, by throwing into relief “the erotic expansion surrounding immateriality” – that is, a loving relationship with a being that lacks corporeality – the film sheds light on the weaknesses of dualistic thinking that opposes man and machine: “The allure of technique is so strong in the film that it reaches a threshold.”

Anthropological changes caused by new technologies were also addressed by Matos, who highlighted the metamorphoses in space-time perception. For her, the digital culture comes with a feeling of that time is being compressed and space is expanding, a sense of acceleration and ubiquity, “as if everything was happening here and now.” This is the digital utopia of ubiquity. “But where are we when we are in many different places?” she asked.

In Matos’ view, we must be cautious when analyzing the impacts of technological resources, because “science and technology do not think, but they do and undo, build and destroy without considering the boundaries between the licit and the illicit, the real and the imaginary.” That is why “the notion that everything modern is ontologically good makes no sense; the body may grow or regress and become fetishized: it thus turns into an object and may be chosen by any technology.”

Photos (from the top): first - movie disclosure; others - Sandra Codo/IEA-USP